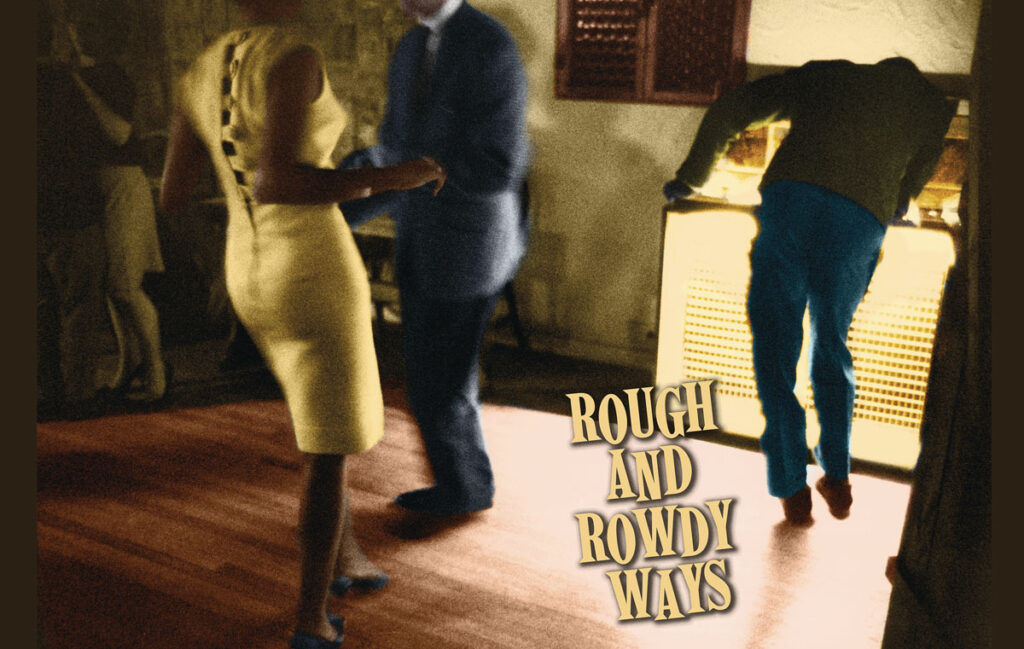

Into Music Review: Rough and Rowdy Ways by Bob Dylan

‘Today, tomorrow and yesterday too.’ So begins ‘I Contain Multitudes’, the first track on Bob Dylan’s Rough and Rowdy Ways, his 39th studio album and first collection of new songs in eight years. Dylan begins where W.B. Yeats, in his great poem ‘Sailing to Byzantium’, ended, speaking ‘Of what is past, or passing, or to come.’ Dylan has been obsessed with time forever. Like Robert Graves, a poet he admires, Dylan treats time as if it doesn’t really exist – while time treats Dylan as if he very much exists. Once Dylan could get away with singing that he was younger than he used to be, now the marvel is that he is still here, writing songs that are better than anyone else’s.

Not that this album is without the (usually twelve-bar) blues-rock fillers that are a staple of any new Dylan album. And this isn’t a recent phenomenon – go back to Dylan at his absolute peak, on 1966’s Blonde on Blonde, and you will find similar: ‘Pledging My Time’, ‘Leopard-Skin Pillbox Hat’, ‘Obviously Five Believers’. On this album the equivalents are ‘False Prophet’, ‘Goodbye Jimmy Reed’, and ‘Crossing the Rubicon’. But ‘fillers’ would be too derogatory a word for songs like these if it wasn’t for the quality of the standout songs. In Dylan’s late flowering, only Together Through Life has been uniformly even with no peaks. When it was released, 2012’s Tempest looked to be the great late album we’d been hoping for, with songs like ‘Narrow Way’ having that rough unstable energy of the great mid-60s albums, and even the same verbal and emotional contortions in lines such as ‘If I can’t work up to you, you’ll surely have to work down to me someday.’ But it was as if Dylan was setting out to disprove the thing he’d said himself, movingly, in a 2004 interview about his ‘magical’ early songs: ‘I can do other things now, but I can’t do that.’ And, impressive though it was, there was too little emotional pressure behind the album’s title song to prevent some of its many verses from descending into bathos and doggerel.

Rough and Rowdy Ways doesn’t have the rage, spilling over into meanness, that gave Tempest its edge. But it has something better: wise vulnerability, in alluring melodies and in lines such as ‘I’ve already outlived my life by far’ (‘Mother of Muses’) and ‘My heart is at rest, I’d like to keep it that way’ (‘Black Rider’). Yes, there are the mad, self-aggrandising lines like these from the opening track:

You greedy old wolf, I’ll show you my heart

But not all of it, only the hateful part.

I’ll sell you down the river, I’ll put a price on your head.

What more can I tell you?

I sleep with life and death in the same bed.

How much of this is persona, like those unhinged characters in Tom Waits songs, and how much is it the Lear-like anger of an artist who once had the world at his feet and now has to make do with the world’s grateful plaudits? This style of writing has now become Dylan’s default setting, and the real richness lies in the more nuanced and contradictory ‘multitudes’ that Dylan contains.

The Frankenstein theme of ‘My Own Version of You’ is matched by the song’s grisly descending cadences. Its lyrics have already earned censure from The Guardian for presenting a ‘ghoulish fantasy of a woman without aesthetics of her own, much less a mind’, but that’s a wilfully odd reading of a witty song that talks about piecing together ‘the Scarface Pacino and The Godfather Brando’ – and when later in the song he threatens to ‘use all of my powers’, it’s The Godfather Pacino he is quoting. One suspects that Dylan has watched a lot of movies, or the same movies over and over, in those hotel rooms that he says are his private studio. Despite the title, in which ‘you’ can be assumed to be a woman, the song is more concerned with the persona of manhood that can be cobbled together from movies, literature and religion. The shape-shifting Dylan is acknowledging the unnaturalness of this way of being.

The pleasantly and sparsely arranged ‘Black Rider’, consisting of five solidly written verses and no chorus, alternates between fending off death and coming to terms with it, much as Leonard Cohen did in the songs of his own late flowering. The title of the sweetly melodic ‘I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You’ sets the listener up for more of the same sort of thing as the overrated, much-covered 90s’ track, ‘Make You Feel My Love’. But this is a love song that’s as much sacred as profane, and sounds more like a thoughtful man facing mortality than an ageing star hitting on a young woman.

Who knows how this album will grow in the listening, but the tracks that impress most initially are the opening, penultimate and closing ones. ‘I Contain Multitudes’ is so good that it has already been covered (superbly, by Emma Swift), just as in the old days when artists were clamouring to record Dylan songs as soon as, or even before, he had. ‘Key West (Philosopher Pirate)’ meanders along in a lilting fashion, the place’s name being invoked like a soothing mantra, so that it’s easy to miss the reference to the turn-of-the-20th-century assassination of President William McKinley. And it’s a gentle lead-in to the magnificent, 17-minute-long album-finisher, a song that deserves a review to itself, about another assassinated president who hasn’t slipped from anybody’s mind: John F. Kennedy. A surprise release in late March, with the world in the grip of a pandemic, it has been out long enough now for most of us to have decided for ourselves whether it’s a ‘one-note dirge’ or one of the great songs of the 21st century – one that speaks of the past and of what’s passing (at a time when the office of the US Presidency has been so thoroughly degraded) and will surely speak to those still to come:

Was a hard act to follow, second to none

They killed him on the altar of the rising sun

Play ‘Misty’ for me and ‘That Old Devil Moon’

Play ‘Anything Goes’ and ‘Memphis in June’

Play ‘Lonely at the Top’ and ‘Lonely Are the Brave’

Play it for Houdini spinning around in his grave

Play Jelly Roll Morton, play ‘Lucille’

Play ‘Deep in a Dream’, and play ‘Driving Wheel’

Play ‘Moonlight Sonata’ in F-sharp

And ‘A Key to the Highway’ for the king on the harp

Play ‘Marching Through Georgia’ and ‘Dumbarton’s Drums’

Play ‘Darkness’ and death will come when it comes

Play ‘Love Me or Leave Me’ by the great Bud Powell

Play ‘The Blood-Stained Banner’, play ‘Murder Most Foul’.

David Cameron

davidcameronpoet.com

Rough and Rowdy Ways by Bob Dylan was released on 19 June 2020, through Columbia Records.