INTO ART: Unknown Man by Ken Currie

A collaborative essay written by Loretta Mulholland and Ian Hume on Ken Currie’s portrait of forensic anthropologist, Dame Sue Black.

We talked of this process of combining our thoughts many times, overglasses of wine and packets of crisps in the Phoenix Bar in those Dundee days before Covid. We’ve attended Zoom meetings and creative conversations talking for hours about how to blend writing, WhatsApp-ing our ideas back and forth like the zig-zagging outline of an Eavan Boland poem, capturing landscapes of memories and a weather full of words but we’ve never managed to put our ideas down on paper. Until now.

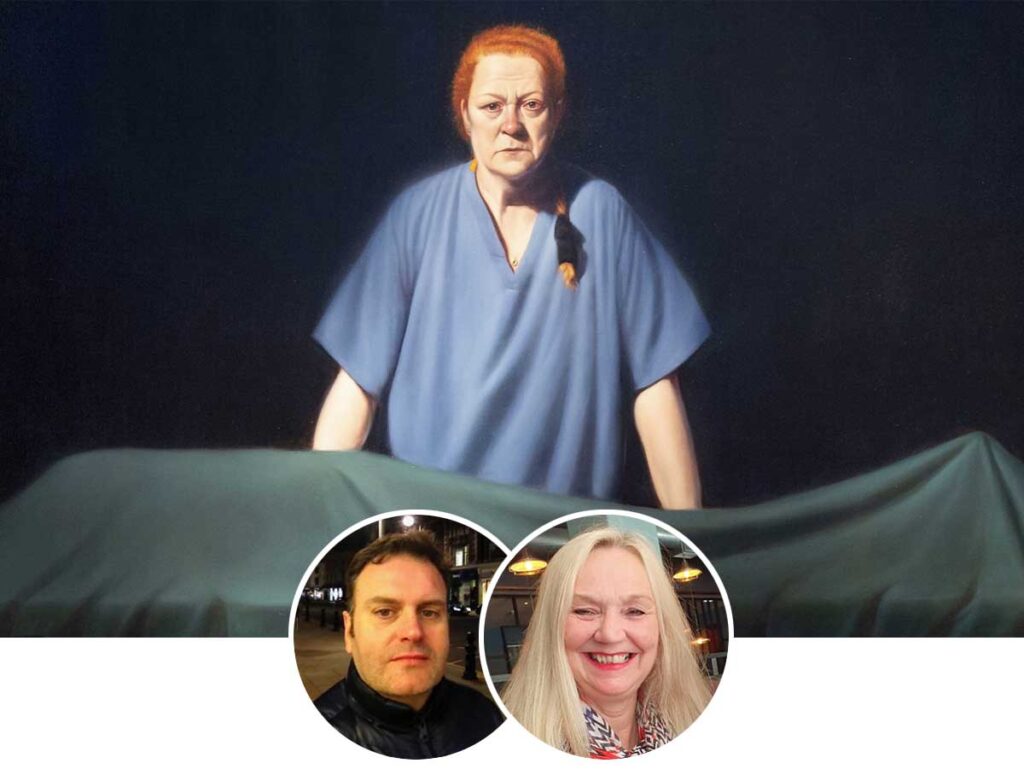

A portrait of Dame Sue Black has been unveiled in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh. The artist is Ken Currie, renowned for his vivid depictions of Clydeside socialism, of the Red Clyde (which now hang rightfully in Glasgow’s People’s Palace) and for being part of the ‘New Glasgow Boys’, known for their vigorous blending of social realism and a myth-making style that was emerging from Glasgow School of Art in the early 1980s. His paintings have a super-real quality; their subject matter relevant, present; their details arresting from a distance. They, their immediacy, offer a context, a way of looking and remembering that combine tenderness with the harshest of realities – in the way poets and writers of their generation have done, and still do.

An online video of the unveiling in the locked-down gallery with the artist shows Dame Sue Black walking away from the portrait before turning round to look at it and expressing, in a cloudburst of emotion, the words: ‘I love it, I really love it’. The painting contains elements of her life as a forensic anthropologist, eminent in her field: a woman whose scrub-blue immanence hangs in wave-like drapes from her torso, suggesting something of her lifeforce. Folds that are also reflected in the green drapery covering Unknown Man, the corpse, perhaps showing the movement, the transition, from life to death. They are ‘different stages of the same process’1, all the way down to the gravity-fed bucket. This is a portrait of a person as much as it is of professional endeavour.

Ken’s paintings have that quality of looking out, of apprehending, of holding you in their gaze – not like some that look right through you to what lies beyond. Instead bringing you into the picture, into the frame with them. There’s a portrait of Donald Dewar, First Minister of Scotland until his death in 2000, by Anne H. Mackintosh hanging in the Scottish Parliament that I visit every now and then. Online, it’s easy to keep a social distance, as ‘the father of the nation’ listens before offering strong words of support, of solidarity, of guidance much in the same way Ken Currie’s portraits do. They share the content of their lives, as much as colour pigment has that ability to share painted realities, mutabilities even.

Looking through the filmy transluscency to the life within it and how it beckons, Three Oncologists, an earlier portrait also hanging in the gallery, lead you through curtains to the threshold of an inner darkness, an abyss, their curved torsos and arms shaping the way, their eyes focused on you in a stern and sinister manner. Unknown Man is formed of the same dark elements. The same motes of dust. Is it magic, alchemy or science. I suspect a measure of both?

Several years ago when my younger nephew, as an infant, was admitted as an emergency to Glasgow Sick Children’s Hospital with a desperate case of croup, he was more upset by what he believed lay in wait in the next room than by his difficulty breathing; the shadows and voices through opaque glazing and not the stridor we could hear or the blue blossoms on his lips. He recovered quickly with a shot of dexamethasone. This artful presentation possesses something of that terror, this blend of science with death.

A sanguinous-red bucket for everything that might drain from the body, the corpse, the object of the painting. A collecting vessel, an urn, a ewer…a sump. You and I talked about the bucket – the one that Oor Wullie sat on. What colour was it? Was it red? No, white – or grey or silver – depending on the publication – or artist – or year. The Sunday Post or the Annuals – one black & white, the other in colour. There’s a red bucket in this portrait. Under a dissection table. Beneath Dame Black.

There is sorrow in her eyes, anger too. A complex blend of emotions. Eyes of one who has looked for too long and too hard at the forensic details of what is hidden, buried beneath the drape (of common understanding).

Wullie’s shirt is sometimes red, contrasting with his black dungarees as he sits on his aluminium bucket, contemplating. An upturned wash-hoose bucket as idle as Wullie. The blonde, spikey-haired lad – already out-of-date when I was his age – who mused on the world of grown-ups and mishaps, his bucket providing a concrete vessel for his metaphysical reflections … bringing you into the picture, into the frame, with him.

And the red nose… emblematic of many of Ken Currie’s portraits. A red-ness that is echoed throughout this one – in her eyes, hair and, of course, as your eyes shift downward to the red of a bucket placed the right way up.

You and I, the onlookers, the silent auditors, the almost-but-not-quite-invited by the subject to survey this most diabolic of spectacles. A dissection.

I dive into this bucket, swimming around, clutching at depths of memories and connections, as Ken Currie must do before he creates, as Dame Sue must also consider, before she dissects. The water is cold, catches my breath. I think of a loch and my father’s near drowning … how he was pulled from the surface that became too shallow to water-ski. How I watched him splatter against rocks, become almost one of Dame Black’s bodies! Still my head swims in that bucket.

And still, my head swims in that bucket of cold silence; light reflecting on atoms of memory as they spread.

Mind pressed by the background uniformity of the deep blue-pleated curtains that you might find in the more vintage viewing salons of hospital mortuaries, as well as theatres; blues seguing into greens, agitated by the percolation of imported images, of Edward Hopper’s paintings, of David Lynch’s films, of externalised angst, of subjects transfixed by thoughts of something other than the situation they find themselves in. An usherette in New York Movie deep in thought while an alternative reality is projected on-screen; or Nighthawks in which late-night diners, deep in shared conversation, reveal the darker tones of their souls over coffee, under excoriations of electric light. Or Mulholland Drive where narrative veers from a sweet dream to the rawest of awakenings. This portrait envelops some of this; all of this.

Still my head swims in that bucket.

Doctors in teal gowns, taking my father away,

My mother in tears of guilt, unaware of what was happening

As she talked to the driver, waves bouncing the speedboat,

Dad skimming shallow pebbled shore.

A TV soap star driving us to A&E in Alexandria as we pondered

If my father would ever walk again

A real life drama

Thoughts of something other than the situation

We found ourselves in.

This portrait envelops some of this; all of this.

Green. Green Gowns. Dear Green Place. West meeting East in Art. Red Clydeside. Iron Foundries. Tin Buckets. Red Shirts. Red Buckets. Black Soot. Black Mills. Black Print. Black Night. Black Death. Sue Black.

Dear Green Place. An abundance of parks. A dream. A place fused between the reality of post-industrial cities like Glasgow and Dundee, where bodies are buried or burned in their thousands, and politicians and medics dissect the reasons – disease, poverty, hard labour, unemployment, hard drinking, drug taking, natural death, infant mortality, old age, murder.

Dear Green Place.

The rawest of awakenings … the something ‘other’ than the situation.

After what seemed like a lifetime in the west, I moved to Dundee and taught in a school that sat on the site of The Broons’ Glebe Street itself. A former Heidie had acquired the actual street sign and kept it hidden away. My hand-drawn illustrated slide of Oor Wullie on his bucket with a speech bubble proclaiming that the said HT’s school was braw got me my first promotion and I was forever grateful to the bairn on his shiny pail – whatever colour it was. That school stands on a hill overlooking the Tay in one of the most diverse catchment areas in the city. It stands on the edge of Baxter Park, bequeathed to the city by the same jute-rich family that produced Mary-Anne Baxter who, at the age of 80, donated £140,000 to University College, (later Dundee University) to promote the education of both sexes. Her contemporary, Thomas Hunter Cox, whose family had the largest jute factory in the world at Camperdown Works, provided funding for the Department of Anatomy and the first Medical Unit at Dundee University. Cox became the Chair of Anatomy and founder of the Students’ Union, aged 27 at the time. The first body arrived in 1889. It was the body of the last person to be executed in Dundee. The man had been convicted of murder and when the body arrived at the university, the neck brace was still in situ…

Vicissitudes, real and imagined, draw me to Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolas Tulp, painted at the beginning of his success and popularity as an artist, and The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Deijman at the end when he was looking more to his laurels. In the first of these depictions, you the body are painted from shadow as remote from me, looking, as you are from Dr Tulp baring the sinews of your left arm for all to see. All fibres of your body dead to the world, to all feeling – for umbra mortis conveys no emotion. Junior doctors view these tendons from different perspectives, different places in space – secret spaces, hidden to others.

How the light in the dissecting chamber refracts through these views, through motes of dust diverting them away from Dr Tulp’s didactic display.

In the later painting, Rembrandt’s style looks freer, less circumscribed than in the earlier one. The eviscerated corpse is depicted sitting rather than supine, head forward with Deijman cutting into the pink succulence of the brain of criminal tailor, Joris ’Black’ Jack Fonteijn, executed for an unknown crime. His shadowy grey skin tones (in the same umbra mortis) bordering on the expressionist with looser brushwork.

The first body arrived in 1889. It was the body of the last person to be executed in Dundee. The man had been convicted of murder and when the body arrived at the university, the neck brace was still in situ…

the neck brace was still in situ…

Dear Green Place.

Dame Sue Black in scrubs a shade lighter than ultramarine is looking out but not beyond her potential audience. Perhaps it reflects her championing of the Thiel soft-fix embalming method, retaining the body’s natural look and feel. Her determination to improve processes, lay her cards on the table, so to speak.

She has the physical bearing not unlike the young woman in Edouard Manet’s painting A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), whose backwards reflection in a salon mirror landscapes her audience but really nothing else other than her indomitable positioning behind an exquisite black marble-topped table is on view. Arms fanning outward augment her authority.

Unknown Man is a painting about intentions: of minds; of honour; of respect; of advocacy; of painful sorrow in her blood-shot eyes; the longitude of hair, plaited and secured at its distal end by a black scrunchie, a reminder that there’s informality here, too. Humour in the red bucket, and how it links its subject with Dundee.

Black and Red. Red and Black.

Dudley D. Watkins communicated life through characteristic graphics but not all of his influences were comic. The Watkins years ran from 1936-69, when he was the artist for Scotland’s most famous comic son, Oor Wullie, reputedly from the posh Broughty Ferry suburb of Dundee and The Broons, the large family who were Wullie’s Dundee neighbours. Arguably though, Watkins did more than make comic history; he took a nation through dark periods of war and depression, separation and anxiety for the future and through the childish pranks of a lad and the light-hearted exploits of Clan Broon, Watkins and the DC Thomson writers and editors depicted a time of almost utopian innocence.

Each of them had purpose. Authority. Presence.

Each of them offered generations a balm, a Thiel

The fun strip also captured a language which was under threat of being swept aside, dissected, covered with a draped flag, like a corpse on a marble slab. I read The Sunday Post from my home in Glasgow and struggled with pronunciation and phonetic spellings not realising I was learning the East Coast language as I laughed my way through the Sunday Fun Section. I stored sayings like Jings, Crivvens and Help ma Boab into a memory box of silly phrases that is still open today and I learnt to spell words like dreich, scunnered and sleekit that never appeared in the Nelson’s spelling or grammar textbooks that we were weaned on. The bairn was a difficult concept for a wean from Glasgow but I got the picture. Guddling in burns by the But’n’Ben became a dream of mine but a muckle plate o mince and tatties was an everyday reality. Michty me!

These pages could speak to their readers as loudly as a Currie portrait.

They – their immediacy – offer a context, a way of looking and remembering that combines tenderness with harsh reality.

Even without the speech bubbles, Wullie and his pals conveyed a way of life that working- class kids couldn’t connect with anywhere else but without The Post several generations may have missed out on a written Scots language heritage. The tenements of The Broons were as real as the ones I inhabited in the west of Glasgow and here was a cultural landscape that I could in part connect to, bringing me into the picture, into the frame with them.

Dear Green Place

Dear Green Place

It was interesting to see the recent trending tweets of the show of solidarity in Kenmure Street, Pollokshields, Glasgow, when a police van with the words ‘Immigration Enforcement’ drove through streets lined with protestors, culminating in the release of the two men being taken by the Home Office. Clips showed the kind of community solidarity that Donald Dewar and the ‘New Glasgow Boys’ would have been proud of, are proud of – naming the men as ‘neighbours’ and not ‘immigrants’.

Is this compassion – this solidarity – the real language that certain Scottish artists portray? An image that ‘life’s braw’ whichever bucket we gaze upon – or from? Whichever bucket we hail from or end up in? Paintings and graphics that are intentionally inclusive?

How movements in space reveal intentions; how death literally at the cutting-edge of science is associated, strongly, with criminality – a pervading theme in Dame Sue Black’s work.

I keep on coming back to what is beneath the surgical-green drape. A crime mystery to be solved? The name, the identity, of the unknown man yet to be discovered? The language he spoke? The people who anxiously awaited the outcome before he became Dame Black’s object? Is this what we see in the subject’s eyes? In a much broader context, is it knowledge, understanding of who we are as people grappling with thoughts free of the arrant ignorance of prejudice and social injustice that are invoked while looking in and around the objects of the painting; how they are arranged, interact, respond to us looking?

…another glass of wine?

Loretta Mulholland is Fiction Editor and reviewer at Dundee University Review of the Arts (DURA). @LorettaMulholl1

Ian Hume is Poetry Editor at Dundee University Review of the Arts (DURA). @ianhume271

Ken Currie’s Unknown Man can be viewed at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery

1 In Memory of Memory, Maria Stepanova, translated by Sasha Dugdale (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2021).