Into Books Review: Dante’s Trilogy by Alasdair Gray

Books: Dante’s Trilogy

Author: Alasdair Gray

Publisher: Canongate

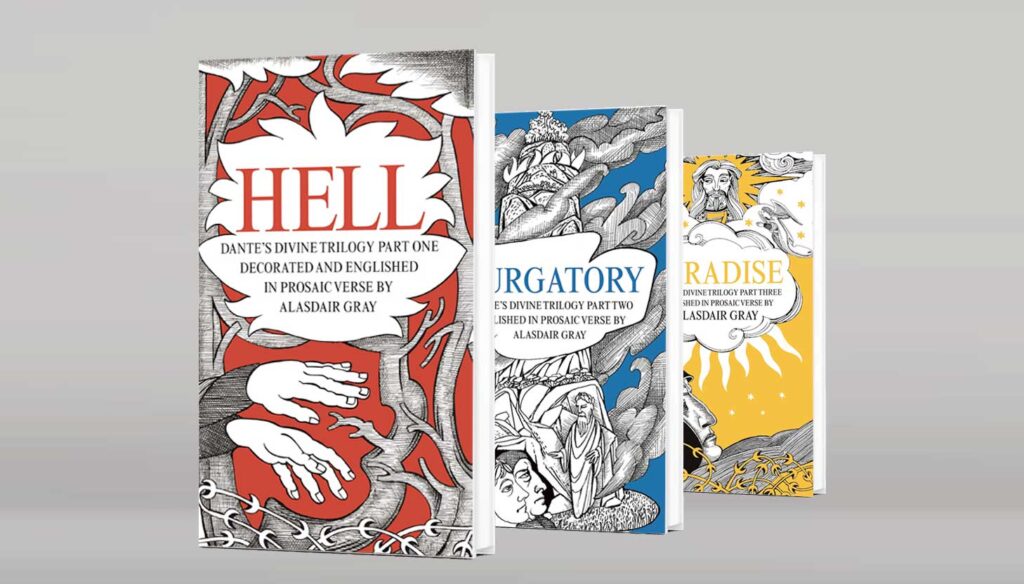

William Blake, an English writer and artist of genius, illustrated Dante’s Divine Comedy but didn’t translate it. Alasdair Gray, a Scottish writer and artist of genius, seemed to be going a step further, both illustrating and translating this medieval masterpiece. But three book covers and a handful of illustrations in Hell aside, we have to make do with Gray’s words only. But, as words go, Gray’s will certainly do.

Dante’s words need time to settle in the mind – to become, in TS Eliot’s expression, part of the furniture of the mind. A review can steer a reader towards or away from the work but can’t hope to contain such multitudes. Fortunately, it’s easy to gauge the temperature of any new translation of the Divine Comedy. Even just the opening line demands that the translator make certain choices which reveal the approach being taken. ‘Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita’ – ‘In the middle of the journey of our lives.’ The time setting is 1300, eight years before the poem was begun, and Dante is 35, a political exile at the midpoint of life’s biblical span of threescore years and ten. He has lost his way, as many of us do in the middle, and is about to go through hell. But does the translator stress the personal aspect of this, or the universal? It is hard to do both. The Irish poet Ciaran Carson chose the personal, rendering this as ‘Halfway through the story of my life’. CH Sisson, whose own great, near-Dantesque poem ‘In Insula Avalonia’ shows how fit he was for the task of translating the Italian master, gets the balance right, with ‘Half way along the road we have to go’, but seems to stumble in the next two lines, as though losing his footing and his way: perhaps an admirable attempt to mimic what is being said, but quite unlike the flow of Dante’s lines. Gray opts for ‘In middle age I wholly lost my way’ – risking the banality of suggesting the sort of ‘mid-life crisis’ that a career change might sort out, but also setting up a direct, confessional tone with a novelist’s instinct for a strong opening line.

Gray has always been more novelist than poet, but his work has a visionary aura that is more usually associated with poetry. The snatches of verse in his landmark debut, Lanark, are no more than a novelist’s idea of poetry. I would have been less excited by the prospect of reading his Dante had I not already read a marvellous, and moving, poem by Gray in the pages of the poetry magazine, The Dark Horse: in the poem, a young son shakes off his father’s hand when others approach in the street – a foretaste of the father-son estrangement to come in later years. Gray expertly conveys the firmly tender and paternal guidance of the poet Virgil as he escorts Dante through hell and purgatory. He has Dante say to Virgil, ‘Please! You know all! Why should I go with you?’ before Dante acknowledges that this is just ‘blethering’. Are these two walking the precincts of hell or of Glasgow?

The question is not dismissive. Gray’s use at times of the Scottish vernacular – ‘my pulse and every sense have gone agley’, etc. – is as justifiable and political a choice as Dante’s to write the original in the Tuscan dialect rather than the expected Latin. Gray is bringing Dante to a contemporary audience, largely in a contemporary idiom, uninhibited by any Scottish cringe.

But these books aren’t only of interest to Gray’s admirers. Take these lines from the opening canto:

A wolf beside him, rabid from starvation,

horribly hungry, far more dangerous,

has driven multitudes to desperation,

me too!…

There’s no mistaking the presence of either Dante or Gray there: Dante for the most part, but that’s surely Gray looking over his glasses and uttering ‘me too!’

Another choice that a translator of Dante has to make is how closely to follow his poetic procedures. This epic is written in one of the tightest rhyme schemes known to man, terza rima (rhyming aba bcb cdc, and so on). Italian lends itself to such prolonged and rigorous rhyming much more readily than English does, but that hasn’t stopped translators from trying. Any good poet can write in terza rima for a short stretch, but persisting with it results in convoluted syntax and forced rhymes. I don’t know what Ciaran Carson was thinking when he applied his talents to this kind of thing:

Chagrined, he smacked his forehead, and exclaimed:

See where my neverflagging flatteries

have got me, sunk up to my neck in shame!

There are some passages in the original that are so innately poetic that the translator’s task is simply not to screw up. A favourite canto among most readers is the fifth of the Inferno/Hell, in which Dante goes easy on the lustful, seeing their sin as deserving the least punishment while ranking the intellect’s calculating act of betrayal (Judas of Christ, Cassius and Brutus of Julius Caesar) as the worst of sins. Gray doesn’t screw up, as Francesca, who had ‘married lovelessly a hard old man’, recalls the moment when she and her lover Paolo first let themselves go:

To pass an idle hour one afternoon

we chanced to read of how Sir Lancelot

was overcome by love of Guinevere.

This youth who never shall depart from me

trembling all over, dared to kiss my mouth.

That book seduced us. There’s no more to say

except, of course, we read no more that day.

This is the kind of sympathetic but unsentimental observation we expect from a short story by Chekhov rather than a 14th century allegory.

Dante’s Purgatory gets a less good press, or at least is often overlooked. For humankind, the whole concept of purgatory has slipped from mind. Yet if we see beyond the theology and medieval politics, Dante’s journey can be seen in modern psychological terms as breakdown followed by purification and ultimately self-realisation. The purging is an important part of the process. And just as the prayers of the living can be effective in easing the passage of the dead towards paradise, we rely at times on the help of others in the largely solitary task of realising our true selves.

Samuel Beckett revered the Divine Comedy, and his favourite canto was Purgatory’s fourth. He identified with Belacqua, ‘a Florentine well-known for being slow’. There is Beckettian humour in Dante’s encounter with this slothful man who looked ‘totally fatigued’, head sunk between his knees:

Belacqua raised an eye above his thigh

and grunted, “Busybody, up you go

now you know why the sun shines on your left.”

Smiling a bit at that I said to him,

“You need not grumble friend. You’re safe from hell.”

Gray also judges well Virgil’s farewell to Dante in Purgatory’s 27th canto, before the role of guide is assumed by Beatrice, the great unrequited love of Dante’s life from when they were both just nine years old, and whom he met only twice. Virgil is telling Dante that he has done all he can for him and is leaving him ‘master of your body and soul’ – in Sisson’s translation. A more literal translation would be ‘I crown and mitre you over yourself’, which Gray sensibly translates as ‘I crown you king and bishop of your soul’. Reviewers of the individual books of the trilogy have made much of Gray’s looseness and deliberate anachronisms (for example, calling the rival political factions of Dante’s time Whigs and Tories) but he deserves credit too for these small acts of faithfulness, capturing the elements of the original while making the work accessible to a contemporary reader.

When Gray’s Hell was published as part one of a trilogy, I had no more expectation of seeing parts two and three than I have of seeing parts two and three of Bob Dylan’s unreliable memoir, Chronicles. Gray worked to nobody’s deadlines, not even his own. But the great procrastinator succeeded with this last great work, though he didn’t live to see the publication of Paradise. The word ‘light’ is everywhere in this book, and Gray’s rendition has lightness and deftness too. Who can resist lines such as these from the twentieth canto:

And as at daybreak flocks of birds will fly

higher to warm their feathers in the sun,

and scattering while others flutter down,

I saw one settle on a nearby step,

seeming to grow more bright with love for me!

or so I thought, but did not dare to speak

till Beatrice said, “Say what you desire.”

If you are looking only for Dante but aren’t fluent in Italian, then all you really need is a prose crib and the occasional glance at the original to get a sense of how the words look and sound – if you know any Romance language, you can make some headway with Dante’s own words. When you turn to a translation you are in the company of two other people, one acting as a helpful guide. Some guides are better than others, of course. Gray might lead you astray at times, but always enjoyably. These books seduced me. There’s no more to say.

David Cameron

davidcameronpoet.com

Hell, Purgatory and Paradise by Alasdair Gray are published by Canongate.