The Velvet Underground Myth? – Grant McPhee

One of the most repeated rock myths is that The Velvet Underground only sold a miniscule amount of records during their brief existence and that it took until many years later for them to find their rightful place in the music history books after being discovered by ‘Punk’.

Something about this story did not feel quite true. Surely a band which was patronised by Andy Warhol, one of the era’s most infamous artists, would have had some higher public recognition back then? If the emerging Californian Counter-Culture was then being written about widely, then The Velvet Underground must have been written about too; and were perhaps also selling more records than we’ve been led to believe. Maybe much of what the music press had led us to believe regarding the initial lack of popularity of The Velvet Underground was just a myth. I thought I’d take a closer look.

Brian Eno famously said that everyone who bought the first Velvet Underground album went out and formed a band. Or did he? Nobody actually seems to be able to find the source of his legendary quote – Quote Investigator took a look and came to the conclusion that infamous and much repeated quote likely came from a remark during a 1982 Los Angeles Times interview:

“My reputation is far bigger than my sales,” he said with a laugh on the phone from his home in Manhattan. “I was talking to Lou Reed the other day, and he said that the first Velvet Underground record sold only 30,000 copies in its first five years. Yet, that was an enormously important record for so many people. I think everyone who bought one of those 30,000 copies started a band! So I console myself in thinking that some things generate their rewards in second-hand ways.”

It’s certainly a great line, and probably true – to an extent – regarding its inspirational qualities anyway. I’m not convinced about it only selling 10-30,000 copies though. Discogs mentions at least 23 pressings of that first album in 1967 alone. That’s a significant amount of pressings for such a supposedly low-selling album.

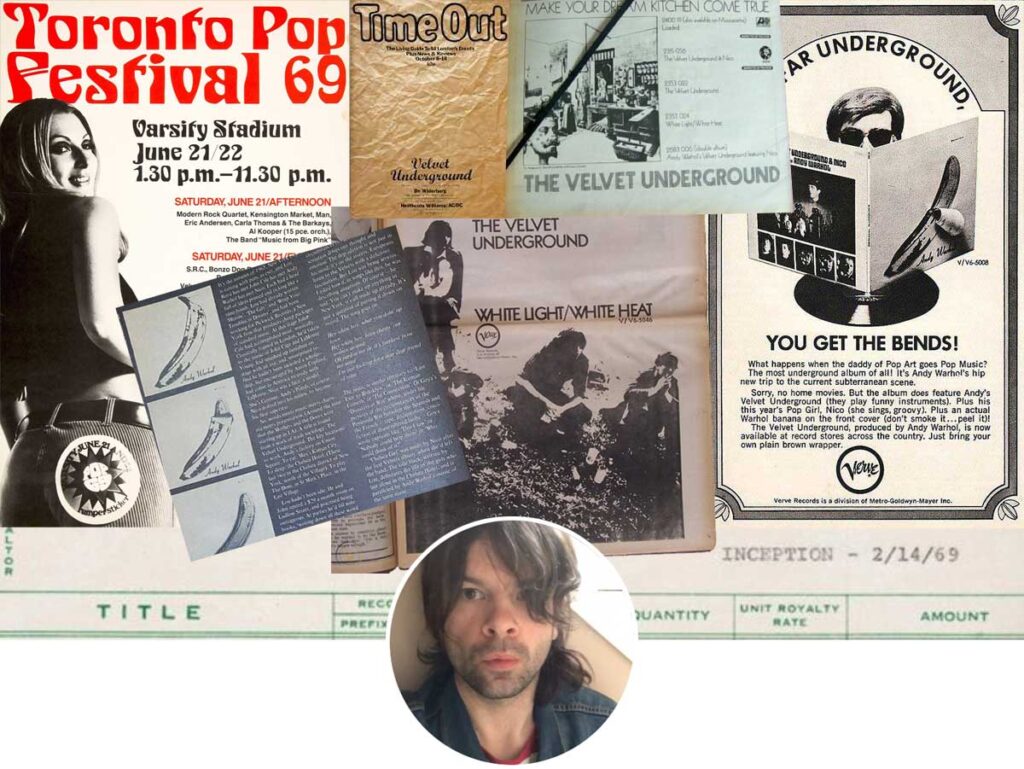

Website RecordMecca has fairly definitive evidence of sales however. The 1967-1968 royalty statement below shows it selling nearly 60K copies. Richie Unterberger also wrote that Sterling Morrison would claim that by 1970 the first album had sold around 200K. 1970-71, which as we will later see, were important years for raising the bands popularity.

We do know that the album reached an original high point of No.171 in the Billboard charts in December 1967 on its 3rd release and stayed for 13 more weeks, comparable to contemporary acts on the same Verve label such as The Mothers of Invention. It almost certainly would have attained a far, far higher position if it had not become the victim of an unfortunate lawsuit during the first pressing. Eric Emerson, a dancer involved with the band, demanded financial compensation regarding an unauthorized use of his image on the back cover as soon as it reached the shops. Verve declined to acquiesce and instead recalled all available copies.

That first pressing had actually entered the charts in mid May 1967 at No. 199 but was recalled in early June. As a stop-gap for getting it back into the shops, Verve pasted over the offending photo until they could later airbrush it. That second release unfortunately came out 5 months later but still managed to reach 182. That delay surely would have impacted on those initial sales and press coverage. What use was publicity or word-of-mouth if there were no records to sell?

Selling 60,000 copies was respectable for an era where the 7” still ruled. In the UK especially, albums were certainly not cheap. The Beatles 1966 studio album Revolver would have cost around £35-40 in 2021 prices, around a quarter of the average pay-cheque of a 16-24 year old in 1967. Just one year later, in 1968 The Beach Boys ‘Friends’ sold only 150,000 copies and only reached No. 126 in the Billboard chart. Other than Sgt Pepper, it would not be until the 1970s when albums sold in the vast quantities that made musicians multi-millionaires, but you didn’t need to sell huge amounts of records to be written about in the 1960s.

Of course, by virtue of being managed and promoted by Andy Warhol, who was a household name in 1966, they were being written about in the mainstream long before any album came out.

One of their earliest performances was reviewed in May 1966 by Philip Eastwood for the San Fransisco Examiner:

Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable, this weekend’s feature at the Fillmore Auditorium, was hardly a revolutionary experience for San Franciscans long used to rock-dances, visuals, black and strobe lights, and other gimmicks of a happening. But some aspects of the EPI were innovative and fascinating.

Two electronic-instrument groups (not really bands) provided sounds for the show and for occasional dancing. Although neither The Velvet Underground or The Mothers is strikingly impressive as a solid-beat dance ensemble, that is not their primary role with Warhol anyway.

Danny Fields would write about them, again in May 1966 but citing an earlier performance from April– and with a little extra history:

It is April, 1966. Warhol is now an international celebrity, reigning soft and strong o’er the New York pop-art, underground movie, and uptown hippie scenes. The triple crown. Well, it would be enough for almost anyone, but it is time to add another scene. So Warhol gets himself a rock group – the Velvet Underground – which has been fired from club after club for being too far out. He puts the group in an abandoned Polish catering hall, surrounds them with (or submerges them under) moving lights and slides and strobes and films and whip-dancers; and thus he brings a new scene to the old town.

The Plastic gets booked into The Trip in Los Angeles. On opening night, April 1966, Hollywood’s pop aristocracy turns out en masse to see it. The Queen, Cher, walks out, telling a reporter, “This will replace nothing, except maybe suicide.” Cass Elliot, who will soon be The Empress of LA, digs the show and comes to The Trip many times while it is booked there. Andy meets the more aggressive Hollywood celebrities, like Jennifer Jones, but Cass simply leaves each night when the show is over. They do not meet.

Even in the UK, Norman Jopling was writing about them in high-street weekly Record Mirror on 22 October 1966 –

The Velvet Underground (this group is handled by film-maker Andy Warhol, who is responsible for many major ‘happenings’ in the U.S.).

One of the earliest album reviews by Richard Goldstein in The Village Voice again mentions the Warhol connection; clearly the front cover he designed would also be a major promotional tool in gaining critical interest. Goldstein was quite mixed about how good the record actually was: ‘The Black Angels Death Song is pretentious to the point of misery’. Importantly though, in addition to the positive words about ‘Heroin,’ it discusses the writers repeated experiences of seeing the band perform live:

Most important is the recorded version of ‘Heroin’, which is more compressed, more restrained than live performances I have seen. But it’s also more a realized work. The tempo fluctuates wildly and finally breaks into a series of utterly terrifying squeals, like the death rattle of a suffocating violin. ‘Heroin’ is seven minutes of genuine 12-tone rock ‘n’ roll.

Back in the UK, Mick Farren had mentioned them in The International Times in 1967, and the album was reviewed in Disc and Echo:

Their music is hard rock ‘n’ roll brought up to date with electricity. An electric viola adds a distinctive cruel, harsh note — it’s particularly evil on ‘Venus In Furs’ and ‘Heroin.’

The UK and The Velvet Underground would cement their special relationship very early on: David Bowie’s early manager Ken Pitt would acquire Norman Dolph’s acetate from Warhol in 1966. As a result, while not the first to cover a Lou Reed song (that special credit goes to Downliners Sect in 1966), Bowie did a semi-cover of I’m Waiting For The Man in very late ’66. Here’s a recording by him and The Riot Squad –

Perhaps the greatest ally to bringing The Velvet Underground into UK mainstream consciousness was Guardian critic Geoffrey Cannon. Through 1968 to early ’69 he’d written profusely about them in the pages of that paper:

Warhol lit on the Velvet Underground as a rock group quite unlike any other, notorious for atonal discords which refused any aesthetic context, and for their delineation of a purgatory of mainline imagery’.

Meanwhile, in the US, Lenny Kaye started name dropping them during his Stooges review and MGM, after loosing Warhol, had been investing heavily in mainstream adverting, such as this full page advert in Rolling Stone for White Light / White Heat in 1968.

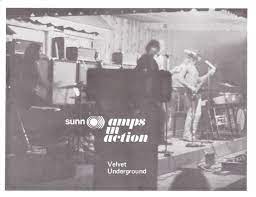

The VERY LOUD amplifier manufacturer, Sun O))) also took out some full page adverts:

Record sales and press coverage is one thing but concerts, festivals and venue sizes are equally as important in determining the popularity of a band. The Velvet Underground seemed to be doing relatively well here too.

In February 1969 they performed with The Grateful Dead and The Fugs at the Stanley Theatre with similar billing. The Grateful Dead were then fast becoming a major live attraction:

Dead of the Day had this to say about the event:

First, the Andy Warhol-managed, Lou Reed-led, antithesis of the Grateful Dead, the Velvet Underground, opened each time, blasting the crowd with their high volume music. It was so loud that one attendee, “FanSince68,” says on Archive that the only reason he can still hear is “because someone near me brought extra cotton balls.” It seemed they played phenomenally though, with a reporter claiming the music was “loud enough to reach the inner core of being without shattering the transcendence of community.

In June they played The Toronto Pop Fest, again with high billing along with Sly and the Family Stone, Dr John and Chuck Berry.

Later in 1969, The Melody Maker had their turn in what may be the first Velvet’s retrospective:

The Velvet Underground have made just three albums, none of which have sold particularly well in Britain. But that trio of albums constitutes a body of work which is easily as impressive as any in rock … If you doubt that statement, then it’s unlikely that you’ve listened hard to the albums, because they yield up their treasure only to a listener who is prepared to treat them with respect and intelligence.

Again, Geoffrey Cannon continued to use his public space to tirelessly promote the VU to the UK public across 1970. Meanwhile in the US, the New York Times used a review to offer another little history piece on the band:

The Velvet Underground was playing experimental rock in 1965 when the Beatles just wanted hold your hand and San Francisco was still the place.

Their cultural significance was also starting to become recognised. Robert Greenfield wrote for Fusion in March 1970:

[The Velvet Underground] Opened up the East Village, changing it from a quiet, unreachable-by-subway neighborhood of Polish dance-halls and burlesque bars into the death-rap freak center of New York that it is today.

Nico, was also being written about extensively during the period of The Marble Index, often referencing her time in The Velvet Underground.

The sleeve of the Velvet Underground’s first album was dead right when it read “Nico: chanteuse.” Not just “singer,” because Nico is more than that, and the word “chanteuse” contains just the right registrations of the European tradition of chanson.

In December 1970, the first re-releases of Velvet’s material began. Vernon Gibbs, in the Columbia Daily Spectator reviewed their first compilation.

One of the most pleasant surprises of the year comes strangely enough from MGM Records. MGM has a series entitled the Golden Archive Series which, attractive as it may sound, is only an excuse to re-issue the material of some of their former artists, many of whom have long left the label due to the incompetence of the MGM management… This is the finest album I’ve listened to this year. The song order couldn’t be better, themes follow in sensible order, moods shift slowly and sometimes an aura can be built around a particular sequence’. Regardless of the significance of The Velvet Underground being compiled after just over 3 years of recording existence it shows that MGM had enough faith in their sales to release a compilation.

On Christmas Eve, Lenny Kaye finally reviewed Loaded for Rolling Stone, their fourth and most heavily mainstream reviewed album:

Lou Reed has always steadfastly maintained that the Velvet Underground were just another Long Island rock ‘n’ roll band. But in the past he really couldn’t be blamed much if people didn’t care to take him seriously.

With a reputation based around such non-American Bandstand masterpieces as ‘Heroin’ and ‘Sister Ray’, not to mention a large avant-garde following which tended to downplay the Velvets’ more Top-40 roots, the group certainly didn’t come off as your usual rock’em-sock’em Action House combination… Well, it now turns out that Reed was right all along.

In 1971, Geoffrey Cannon used his credentials to run a huge in-depth retrospective of the band in Time Out. This coincided with a large re-release campaign by MGM of all albums to tie in with Loaded:

As we know, Lou had left the band before Loaded was released. Management sent Doug Yule out in his place to tour Europe extensively and promoted him extensively and furthering The Velvet Underground myth. Unfortunately by then The Velvet Underground were over but that myth was now in full progress.

While never being on ToTP, I think it’s safe to say that unlike popular claims, The Velvet Underground, in their first few years actually sold a fair few more records than we thought and had a good deal of major press. Figures such as Geoffrey Cannon understood their significance early on and along with Lenny Kaye, started laying the myth for generations from as early as 1968. The Velvet Underground were always going to have a huge impact on popular music.

Grant McPhee

@GrantMcPheeFilm